Dr. Andrew Perriman has penned an excellent post and review of my book Constantine and the Divine Mind (Wipf and Stock 2019) [here], and his assessment has stimulated further thoughts in me regarding pagan monotheism in Constantine and Paul.

As Perriman notices, reading the Constantinian saga in light of a theological metanarrative available in late antiquity (what I call the “decline of monotheism narrative”) proves helpful in charting not only the development of a pagan Constantine’s interest in the god of Christianity (and the political expansion of Christendom which followed), but the philosophical expansion of “orthodox” Christian theology—a realm whose borders came to include a peculiar and surprisingly useful Graeco-Roman metaphysics.

As I argue in the book, Constantine’s role in this process of extension (more central than some Christian theologians have wanted to admit) was spurred by his own theological reflections on a then-current theory about the history of religion which enabled pagan-Christian interpenetration across an axis of monotheism. Constantine’s reading of the Christian story of God’s anointing of Jesus for the conquering/restoration of the world, and his own subordinationist reading of their metaphysical relationship (an interpretation which I’ve also argued for in an article in the Journal of Early Christian History (Routledge/UNISA) [here]), ultimately involve a degree of politically-savvy-but-sincere theological creativity. His interjection at Nicaea of a commandeered Hermetic model, stripped it of its well-known materialistic connotations, was driven first and foremost by a program of world-wide monotheistic restoration, a decisive action which produced simultaneously an expedient (though momentary) resolution of intra-Church conflict and a novel articulation of the Son’s relationship to the Father (see also Vladimir Latinovic’s “Arius Conservatus?,” 2015 [here]). This maneuver formed also a necessary bridge between pagan and Christian worlds—two apparently disparate religious spheres which, as Perriman also notices, each retained acutely “political” visions of a global, divinely-ordained civilization. Perriman’s impression is that my historical proposal has therefore filled a gap in “the process by which the early church got from the proclamation of the coming kingdom of God to the postulations of the Nicene Creed” (what he also rightly describes as a “disjunction” that is easily felt between “the prophetic-apocalyptic interpretation of Jesus’ death and resurrection and the rationalisation of his relation to the Father that became Trinitarian orthodoxy”).

Perriman’s post also describes other ways in which my account has opened up new pathways for both historical and theological travel. He first of all finds in the historical-ecclesiological narrative of Christianity (which at some point clearly “pivots from kingdom towards Trinity”) that the NT’s underlying kingdom narrative was “not yet supplanted by philosophical argumentation” at the time of Nicaea but is still able to be detected in Constantine’s this-worldly eschatological dominionism. This was certainly the view of Constantine’s Christian biographers (e.g. Eusebius) who saw in him not merely a faithful continuation of a fundamental Christian ethic but a divinely-ordained finish to the earthly work of Christ. This theological interpretation of Rome’s religious transition in this period, which will doubtless seem “absurd and parochial” in the eyes of a modern Christendom which doesn’t care about history (to use Perriman’s words), was a living reality for the bishops who awoke from the dark night of the tetrarchy and found themselves suddenly in Constantine’s sympathetic care.

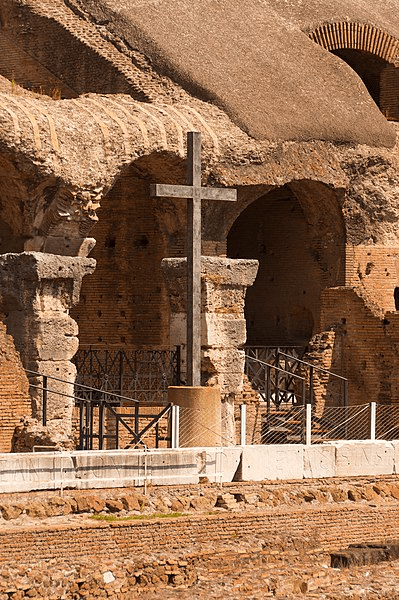

One can understand the power of this outlook without subscription. I remember standing in Rome and observing the many pagan sites converted into Christian churches (e.g. the Colosseum—once a place of Christian suffering now housing at its focal point an austere but tremendous cross), and finding resonance with the Eusebian impulse to discover something miraculous about this transformation. Despite whatever significance contemporary theologians are able to locate in this historical claim about continuity between the missions of Christ and Constantine, Perriman sees that its way had already been “bent by the massive gravitational pull of the pagan monotheism that Chandler describes.”

Even more interesting (for me, at least) is Perriman’s notice that “the overarching aim of Constantine as a pagan monotheist was not so different from Paul’s as an apostle of the God of Israel.” Additionally, he points out, the OT prophets (e.g. Isaiah 45:22-46:2) have in view a world in which the nations dispense with their accumulated traditions in submission to an overwhelming monotheistic rule while nevertheless remaining gentiles. Perriman writes:

“It is important to say that in the Old Testament eschatological perspective the nations as nations do not become part of the people of God, with the exception of some individual proselytes. They remain separate peoples, but they are now oriented religiously towards a restored Jerusalem and its temple, and Israel becomes what it was always meant to be—a royal priesthood for the nations. Arguably, in this eschatological paradigm, a pagan monotheism remains operative.”

While Paul’s antagonism with the idolatrous dimensions of the Roman world is unmistakable, Paul’s sympathies with Roman religion are easily obscured by a prevalent dichotomy erected in the popular sphere (and regretfully perpetuated by theologians and even some historians) of a “monotheistic Christianity” and a flatly “polytheistic Rome.” These totalizing images conjure for most a Roman religious consciousness antithetical to that of “the Bible”; nevertheless, Paul’s letter to the Romans, configured primarily towards a gentile audience, speaks favorably of a time when their ancestors (i.e. pagans) rightly “knew God” before exchanging their accurate knowledge and their noetic worship for a misguided, sensory iconism resulting in the just and “unnatural” social and psychological desserts which had so long encumbered their society (Rom. 1:19-28).

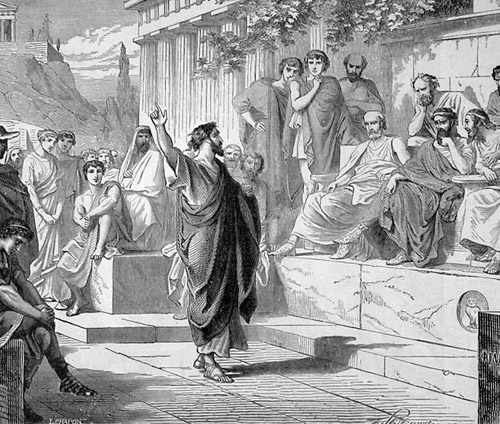

To Perriman’s mutual observation of this point I will add here the complimentary portrait of the Paul of Luke-Acts, who some may be surprised to hear affirms the pious spirit on display at the Areopagus as the production of humans who were “in every way very religious” (Acts 17:23). Rather than turn these pagans in some entirely new direction (i.e. towards some other, heretofore exclusively Israelite deity with whom they have never had anything to do), he relies on an assumption of continuity between Christian and pagan spheres across a (very Constantinian) axis of universal monotheism. Thus Paul’s announcement that this god “whom you worship in ignorance” (and not someone/something else), is “this I preach to you” (Acts 17:23). Paul’s pagans, like the pagan monotheists of Lactantius’ Divine Institutes, have already been tuned in the right direction, though they have gotten some secondary beliefs terribly wrong (e.g. idolatry, blood sacrifice, Hermes Trismegistus vs. Jesus Christ, etc). In Paul’s view, the Areopagites’ theological illiteracy amounts to something like a detached knowing, an epistemic and relational distance which Paul believes that the supreme god, now working through Paul as his spokesperson, demands to be cured. While many pagans in Paul’s day evidently continued to be entirely ignorant of the presence of the supreme god (validating the old prophecy that God’s oneness must be preached at the inauguration of his manifest rule, Zech 14:9), it now seems clear that in Paul’s view some pagans, by way of God’s universal design and the human conscience, had already been compelled to “reach out for him and to find him, though he is not far from each one of us” (Acts 17:28). Indeed, those religionists with whom Paul engaged at the Areopagus had at least been successful in ‘finding’ God, in ‘touching’ God, but had yet to ‘know him’ in the way that they now should or even in the way their pagan ancestors once did. Thus, in Paul’s view, Areopagite religion was still a blind grasping at the hem of God’s garment.

It may be tempting here to echo John G. Saxe’s use of the Buddhist/Jain/Hindu parable in which the men of Indostan run into an elephant (God) and mistake it for a “wall”[see here]. However, the Roman pagans, feeling in the dark alongside the men of Indostan, were evidently not nearly as blind. They may not have seen clearly, according to Paul, but they knew at least that they were feeling an elephant (i.e. a “god,” even a “creator god”). Indeed, it is pagan ignorance to only some thing(s) about this god (namely, how this god is to be approached), not an ignorance of his presence or a complete unawareness of any of his qualities (e.g. his status as the creator/parent of human beings), which receives the brunt of Paul’s apologetic.

Again, as Perriman notes, Paul and Constantine are surprisingly similar. Theirs is a likeness which extends to a belief in the stabilizing effect of aniconic monotheism on human society, and also to a belief that they are able to work effectively to bring about a monotheistic restoration imagined by both pagan poets and Israelite prophets. Indeed, Paul’s Pharisaic view of the world to come, predicated on the promises of the OT, looks forward to a time when the God of Israel will conquer the barbarous nations of the world—a physical, political takeover which includes a domination of the world’s religious consciousness. Indeed, Paul (and Isaiah) hope for a day in which “many peoples” will go up to the mountain of the Israelite god and “learn his ways,” a time when the one god becomes the universal god through a world-wide program of international theological education (Isaiah 2:2-11).

Like Constantine, Paul sees himself as an integral player in a presently-unfolding enlightenment, and furthermore as continuing the messianic mission of Jesus of Nazareth. In Acts 13:47, an Isaianic prophecy elsewhere applied to Jesus’ illumination of the gentile world (Luke 2:32) is taken up by Paul as a reference to his own evangelism. Ultimately, Paul, as “the Pagan’s Apostle” (as Friedriksen described him), and Constantine, the pontifex maximus of Rome, both aim to embody this prophesied “light to the gentiles,” though their approaches differ in various ways. Paul is a minister of a New Covenant encompassing both Jews and Gentiles. Constantine, at least initially, stands apart from such ministers in a position as both priest of Sol Invictus and “bishop of those outside the church” (Eusebius, Life of Constantine 4.24). Though having different starting points, their overlapping worldwide aims involve the monotheistic subsumption of the other’s religious heritage—a fascinating historical and theological overlap worthy of future consideration and comment.

Thanks again to Dr. Perriman for his insights. I hope that Constantine and the Divine Mind continues to generate new avenues of discussion along these lines.

Constantine and the Divine Mind is available from Wipf and Stock publishers [here].

Leave a comment